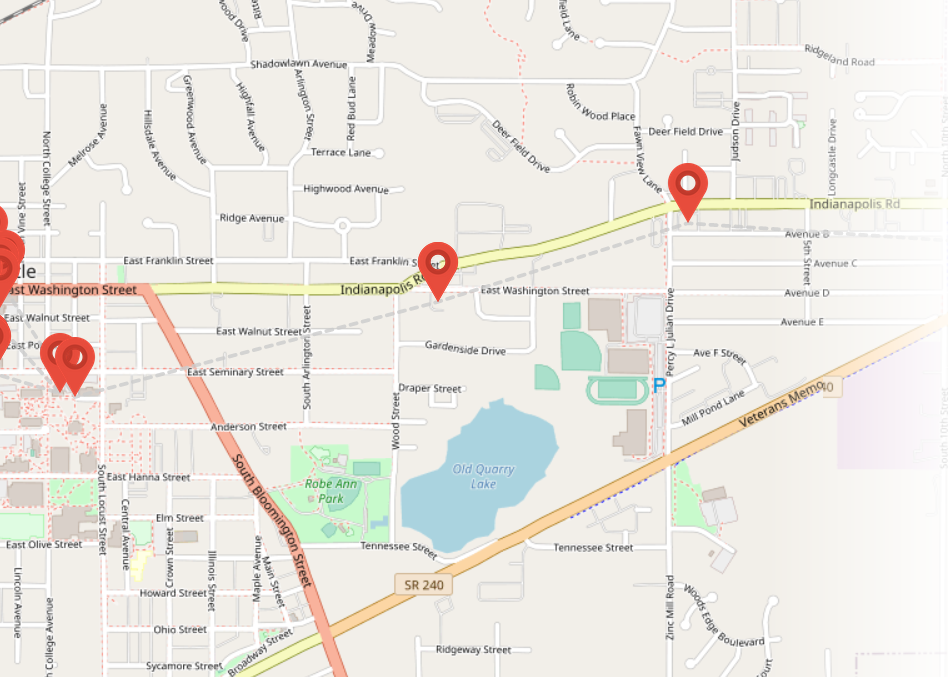

Click here for an interactive StoryMap

Greencastle is a small city of about 10,000 residents and boasts just over five square miles within its limits. I have built a presentation through the Knight Lab StoryMap Program, showing areas that have been most noticeably affected by the pandemic. I find it striking that there have been relatively few changes in Greencastle, Indiana, since Covid-19 came to town. A few businesses have closed, including China Buffet (although it was struggling before the pandemic hit), a small, locally-run boutique, and the Family Video store. A few businesses have opened, including a medium-sized bakery that serves both restaurants and individual customers, another boutique or two to replace the one that closed, and a few restaurants. Businesses generally all have signs requesting customers to wear masks; some customers and employees follow the guidance while others refuse or keep their masks around their chins. Some larger events, such as the city’s First Friday festivals, have still not returned and the small, two-screen movie theatre remains closed. The library has expanded its offerings for check out while also limiting its in-person services. For the most part, however, these seem to be almost cosmetic changes (with the very notable exception of those who were employed at these establishments).

During the warm months of the pandemic, Greencastle closed down a portion of Indiana Street near the downtown square and along a strip with multiple restaurants. This area became a place where families could order food from the restaurants and eat outside while their children danced and cartwheeled up and down the street. The closure was met with mixed reactions, partly because only one establishment, Moore’s Bar, took full advantage of the opportunity. Moreover, the closure was just down the street from the Greencastle Fire Department, forcing the truck to circumvent for any calls in that direction. The article by Hemme and Chamberlain (2020) mused on more permanent redesigns of streets as places for humans to socialize or travel using nonmotorized means. It definitely seems that after the pandemic, residents will be seeking out ways to socialize.

In many ways, wearing a mask has become a visible shorthand for a person’s political leanings. Even more so, signage has served as a social act entrenched in politics and power (Trinch and Snajdr, 2020). It is interesting to think about how signage has been used in the context of the pandemic. Many of the photos within this story map focus on signage as this is the most visible change to the Greencastle landscape that still remains after more than a year of the pandemic. One of the requirements outlined in Indiana Governor Holcomb’s pandemic mandate was that most businesses and employers were obligated to post signage, particularly requesting patrons and employees to wear masks. I found that – at least in Greencastle, but I suspect this was the case in other places as well – while almost all businesses complied with posting signage, actual compliance with mask-wearing varied widely. For example, upon visiting the Moose Lodge with a friend, I noticed that while the establishment had signage prominently posted in multiple places requiring masks, only one young server actually was wearing any kind of face covering. At many other retail locations, many customers carried a mask in their hand but did not actually wear it. By contrast, restaurant on the DePauw University campus and many of the boutiques near the city square, at least strongly encouraged mask-wearing, and I rarely saw anyone without a mask.

There are other ways that signage has acted as a marker of an organization’s stance on current events (most of which seem to have turned political within the last year). Take, for example, the sign in the window of Gobin Memorial Methodist Church that reads, “Resisting evil, injustice, & oppression in whatever forms they present themselves.” The sign is written in white and red text on a black background, which is at least reminiscent of many Black Lives Matter signs. While there is no explicit political leaning stated, there seem to be implications of an awareness and support for endeavors that fight racial injustice, which has become so much more apparent during the pandemic (Hardy 2020).

Another sign on the side of Gobin Memorial Methodist Church reads, “Love is not shut down.” This seems very similar to the messages circulating in many forums that basically amounted to, “We’re all in this together.” There were some clear attempts at promoting community support, such as the Putnam County Mutual Aid: COVID-19 Response group on Facebook where members were encouraged to request or offer any material items or services that could be classified as a basic necessity. Public leaders also attempted to promote these positive feelings in their “Mask Up Public County” campaign, and some businesses put out positive messages, as well. Whether the intention of the marketing campaigns was sincere or opportunistic, the commodification of ideas surrounding connection and community risk masking serious issues and preventing them from fully being addressed (Sobande 2020).

In addition, it is clear that while the pandemic has forced most of us to reevaluate the way we live life day-to-day, it certainly has not affected everyone equally. Shannon Mattern (2021) describes how some were able to retreat while others were not. This was also the case in Greencastle. Some were able to almost entirely retreat because of those who kept working in-person, such as grocery and pharmacy employees, delivery drivers, and restaurant kitchen staff (Mattern 2021). Another factor to being able to retreat came in the form of access to high-speed internet (access both in terms of the availability at my location and the money to pay for it). Not everyone was so fortunate. As Linda Poon (2021) described about the “Digital Divide,” many homes remain without reliable internet. This not only affected adults’ ability to work from home, but also school children’s ability to learn. Issues of inequitable access became much more real to many who had never considered it before.

This brings us to the end of our neighborhood tour of Greencastle, Indiana. It is still difficult to say which changes will be permanent within the city and which will revert back to “normal.” There definitely seems to be an eagerness and longing for a return to routine. Some of the fear, though, seems to have been exacerbated by the deep divides within the community about a subject that has become surprisingly partisan: healthcare and overcoming a worldwide crisis. Instead, in many contexts, mask-wearing has become code for one’s political stance. Signs have become displays of defiance, compliance, or attempts at transmitting messages of unity. Even creating more outdoor public space has become a source of contention. The time of the Covid-19 pandemic has stretched into a form of collective stress and trauma. Maybe it is not so surprising that during “The Great Pause,” (Mattern 2021) Greencastle and much of the rest of the world has had time to realize just how divided the country is on issues of healthcare, racial justice, and the general public good. Hopefully, this wrestling and conflict will ultimately lead to lasting changes for the good of our community and communities everywhere.

References

Hardy, Lisa J. 2020. “Negotiating Inequality: Disruption and COVID-19 in the United States.” City & Society by the American Anthropological Association: 1-9.

Hemme, Dan, and Bruce Chamberlain. 2020. “Beyond Complete Streets: Could COVID-19 Help Transform Thoroughfares Into Places for People?” Planetizen website, September 7. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.planetizen.com/features/110429-beyond-complete-streets-could-covid-19-help-transform-thoroughfares-places-people

Mattern, Shannon. 2021. “How to Map Nothing.” Places Journal website, March 2021. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://placesjournal.org/article/how-to-map-nothing/

Poon, Linda. 2021. “To Bridge the Digital Divide, Cities Tap Their Own Infrastructure.” Bloomberg CityLab website, Feb. 8. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-08/cities-try-new-ideas-to-narrow-digital-divide.

Sobande, Francesca. 2020. “‘We’re all in this together’: Commodified notions of connection, care and community in brand responses to COVID-19.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (6): 1033-1037.

Trinch, Shonna L., and Edward Snajdr. 2020. “Introduction: Discovering a Field Site.” In What the signs say: reading a changing Brooklyn, 1-31. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.